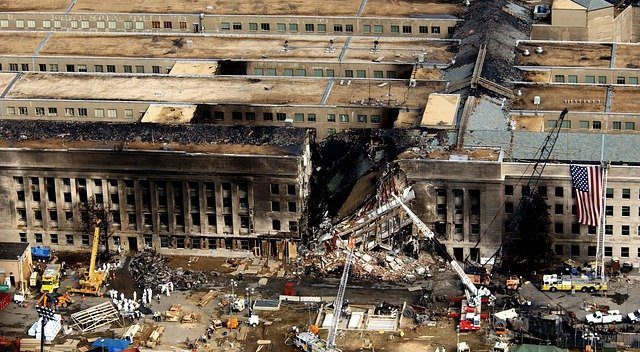

Sower Advisor Shares Own 9/11 Story

A section of the Pentagon buildings lays in shambles after Flight 77 crashed into the building, claiming 189 lives in total.

by Ellen Beck

Sower Advisor

Many journalists who worked in New York and Washington, D.C., on Sept. 11, 2001, when terrorists flew planes in the World Trade Center towers and the Pentagon, have incredible stories about the reporting they did that day. For me, however, that day was all about a tourist family from Canada, commandeering a shuttle bus, running scared from the National Airport terminal building as fighter jets buzzed overhead, and thoughts and concerns about my 9-year-old fourth-grader, JT. And yes, I did some reporting, too.

When I left our home in Burke, Va., that morning to drive to the Metro station in Springfield and pick up a train to downtown D.C., I knew that one plane had crashed into one of the WTC towers, but not much else. At that point, to me, this was a New York story and I didn’t necessarily assume a terrorist attack. I had a brief thought of a small private plane getting turned around and accidentally hitting the building. En route, I remember the DJ on my favorite ’70s radio station breaking into the music to say a second plane had hit the other WTC tower. My concern ratcheted up, but still, it was a New York story and I worked in Washington for an international wire service, United Press International, that was well-equipped to cover it. I was on the train to D.C., via National Airport and the Pentagon, when a plane hijacked by terrorists flew into the Pentagon and everything changed.

A mother and two children from Canada had struck up a conversation, asking me about what attractions to see in downtown Washington and I rattled off the usual list of the Smithsonian, Ford’s Theater, the museums, and the Washington Monument. It was not unusual for tourists on a Metro train to ask for advice from people they perceived as locals and I often had given out the name of a good restaurant or directions to some destination.

When the Pentagon got hit, my mom called my cell phone and told me, and I quickly told my new Canadian friends, knowing even that early on that D.C. would be locked down and everything closed. I remember getting annoyed at the young son who gave me considerable pushback, complaining that he wanted to continue with their day of sightseeing.

My thoughts were scattered. I knew my husband, CUNE’s Professor Tobin Beck, at that time executive editor at UPI, was in the office and I had all the confidence in the world he would have coverage of all these events well under control. Looking back, he did, filing more than 300 stories in a 24-hour cycle without any mistakes. He is the consummate journalist and professional. But I also knew he wasn’t going to be home for dinner that night — and my guess was that it might be a couple of days before I’d see him. I assumed that access to the downtown area where our office was, one block from the White House, would be shut down for security purposes and, indeed, later a colleague told me there were armed soldiers on the streets, especially around the White House. Anyone leaving the office would not get back in.

I had to go home. JT’s school most likely would be on lockdown — and it was — and I would have to pick him up in person, likely showing identification. The train at this point pulled into National Airport, so the next stop would be Crystal City — named for its long line of tall, glass-enclosed office buildings — and then the Pentagon. Usually, the train pauses at a stop only long enough to let people get off and board but this train stayed put. After a couple of minutes, I turned to my Canadian friends, who were visibly frightened, and told them I didn’t think we were going to get any closer, that likely the metro stop under the Pentagon would be shut down.

I got off the train, the Canadian family a half-step behind me and not looking like they were going to let me out of their sight. We walked up the hill toward the terminal building so we could try to figure out how to get transportation out. It was then that three fighter jets buzzed the top of the terminal, just as a thunderous boom came from the area of the Pentagon and a huge plume of smoke billowed into the sky. Airport officials came out screaming at us not to come to the terminal. The fear was another plane had hit the Pentagon and others may be headed for additional buildings, including the airport. We literally ran back down the hill toward the train, which had emptied out. Later I would later learn the boom was the collapse of a portion of the Pentagon that had been hit.

I didn’t have time to think things through, but I had to get my Canadian tourists safely back to their hotel in Springfield. I caught sight of an empty shuttle bus driving through the airport, and I ran into the middle of the road and put my hand up for the driver to stop. He opened the door and yelled that he wouldn’t take us anywhere. I still remember my words to him: “Oh yes you will! Take us to Crystal City.” And as I stepped up into the shuttle with the Canadian family behind me, about 50 people pushed in and filled the vehicle.

The driver did take us to Crystal City but as we approached, I wondered if I had made the right call. I’m not great at crowd counts but it seemed like thousands of people who were working in those glass towers decided it wasn’t safe to stay and fled to the street. It was chaos, people going in every direction, shoulder-to-shoulder, no one really getting anywhere. In the middle of the road was a lone taxi trying to make its way through the throng. I glanced in and saw just one passenger. So I opened the door and pushed the Canadians inside of the taxi as the driver screamed to me that he would not take any more people. I told him: “Yes you will. These people are from Canada, and they don’t belong here. Take them back to their hotel in Springfield!” With that, I slammed the door, gave them a wave and the taxi inched forward.

I had done the best I could for my tourist friends and my thoughts then turned to what I could do to get home and be there for JT. I wondered if he knew or what he knew. I knew his school had many students who had a family member in the military and/or working at the Pentagon. I worried about what to tell him. He was the son of journalists and talk around our dinner table almost always turned to current events, but this was a lot for a young boy to take in. I didn’t want him to be frightened, but I couldn’t tell him I wasn’t frightened myself.

I made my way to the Crystal City Metro stop and just as I was on the last step of the escalator heading to the tracks, a train pulled in going south. It had to have come from the Pentagon, so I ran and jumped on board. It was packed with people, some looking stunned and sad. After listening to the quiet chatter for a few minutes I realized I was sitting with Pentagon workers who had caught the last train out before the Metro station there was shut down.

The journalist in me took over and I did what came naturally. I grabbed my notebook and pen from my purse and started talking with people, identifying myself as a UPI reporter. I just asked them to tell me what they saw and how they felt. By the time I had gone most of the way through the train car, the train pulled into the Springfield station. I ran to my car and called the UPI editing desk, dictating notes to one of the senior editors, who added what the Pentagon workers told me to the lead story.

I got home to find I had a couple of hours before I had to pick up JT at school so I started watching coverage of the attacks on TV and figuring out what else I could do. I made calls to child psychologists and psychiatrists and at least one medical doctor. I got a few who were in and agreed to talk so I interviewed them about how this attack — and by now we were calling it a terrorist attack — could affect children’s mental health. I had time to write about a 600-word story and send it to the Science desk for editing before I had to head to school, where it was a long wait as each person had to show ID to pick up their child.

JT was quiet and while I tried to talk with him about the events of the day, he didn’t have much to say. He hadn’t seen anything on TV about it and was not told what had happened. He said he heard rumors but nothing else. Later we would find out several classmates had lost family members in the Pentagon attack.

US airlines were grounded for several days but as soon as I could I had my mom fly in from Wisconsin. She ran the household while Tobin and I both worked long hours in the UPI bureau as coverage of the attacks continued. A week later, on Sept. 18, the U.S. was terrorized again as letters laced with poisonous anthrax were sent to people in the mail and five people died. There were also fakes — letters with harmless white powder — some sent to media, including UPI. I transitioned to lead the coverage of the anthrax attacks for the next several weeks.

To this day I do not know what became of the Canadian family, whose vacation to the US Capital turned into a nightmare. I hope they didn’t have too much trouble getting back home. I hope they eventually came back and saw all of the great monuments, museums and historic buildings, which to me were always emblems of our great country but had taken on new significance and meaning after 9/11.