History of Concordia: The Founding and Early Years of Concordia University, 1894-1919

Campus pre 1913; all buildings except Nebraska Hall are included. On the left is Becker Hall (administration and science), then the two White Houses (obviously), Founders, Miessler Hall on the right.

By Dr. Jerrald Pfabe

The following article is the first of the Sower’s ongoing History of Concordia series in celebration of Concordia’s 125thanniversary and our publication’s 55th anniversary. The Sower would like to thank Dr. Jerrald Pfabe for his time and contributions in writing this article.

On the dreary afternoon of Nov. 18, 1894, a crowd estimated at well over 1,000 gathered on the northeast side of the small city of Seward, Nebraska, for the dedication of the new “evangelische-lutherische Schullehrer-Seminar” (the Evangelical Lutheran School Teachers Seminary). The authorization for this new school was an 1893 resolution of the parent church body, today’s Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS), to establish in Nebraska a second teacher education institution. Several communities sought to be the site of the school. Four men from St. John Lutheran Church, Hermann Diers, O. E. Bernecker, J. F. Goehner and Peter Goehner, succeeded in getting the synod to choose Seward. They offered 20 acres of land and $8,000. J. George Weller, pastor of the Lutheran church in Marysville, Nebraska, was called as the director and first teacher in October of 1894. Classes began on Nov. 20 with 13 students enrolled.

The initial academic program consisted of three years of high school. Students who wanted to complete the diploma for Lutheran teaching would transfer to the other LCMS teachers’ institution at Addison, Illinois. Although the school was often referred to as the “German college” locally, English predominated as the language of instruction from the beginning. Room and board was $12 a quarter; tuition was free for those in the Lutheran teaching program.

In the first year of the school, the students and the family of George Weller lived in Founders Hall. Mrs. Weller did the cooking and the laundry for her family and the students. One Saturday, Director Weller decided to help the “boys” with cleaning their rooms. He brought a bucket of water upstairs and dumped it on the floor. Soon, Mrs. Weller called out from below, “Papa, the water’s coming through!” That may have ended his custodial career.

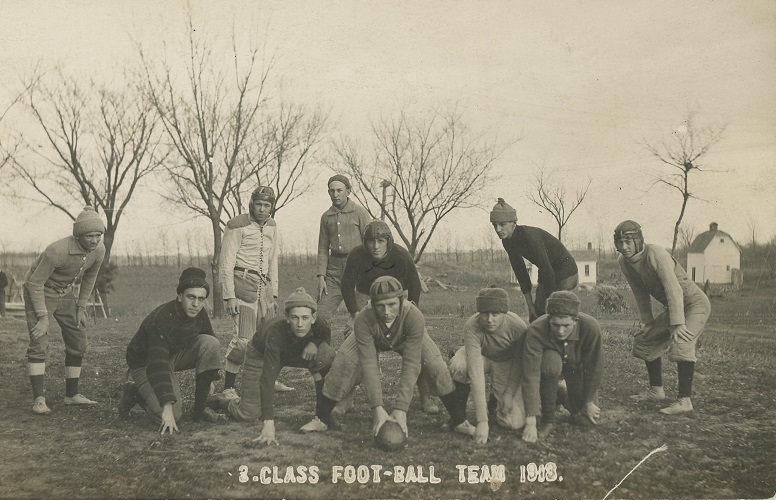

Football team in 1913. This was the team of the senior high school class. Classes had teams and played each other.

Photo courtesy of Jerrald Pfabe

A major change for the young school came in 1905 when the LCMS authorized the addition of two years of college (or normal school) to the program. Students now could complete their studies on the Seward campus and no longer had to transfer to Addison. In 1908, a fourth year of high school became a required part of the curriculum. In those days, all students took the same courses; there were no electives or majors. All students, for example, had to take piano and organ, and, in some years, violin. To staff the enlarged program, the school added additional faculty—seven full-time professors by 1910. These were George Weller, Fred Strieter, Karl Haase, H. B. Fehner, August Schuelke, J. T. Link and Paul Reuter. The physical plant of the college expanded beyond Founders Hall with five new buildings constructed by 1913: Miessler Hall, Becker Hall, Nebraska Hall and White Houses One and Two. A “training school” was established in 1906 on the south side of the campus—roughly where Schuelke and Strieter Halls are today—to serve as the student teaching center. Students from grades one and two and seven and eight from St. John Lutheran Church attended the training school under the supervision of Fehner and Link.

Campus pre 1913; all buildings except Nebraska Hall are included. On the left is Becker Hall (administration and science), then the two White Houses (obviously), Founders, Miessler Hall on the right.

Photo courtesy of Jerrald Pfabe

Outside of the academic world, students enjoyed a variety of activities, such as picnics near the Blue River, the open air concerts in which the band, orchestra and choir performed for the community at the end of the school year, and participating in the annual community Memorial Day parades. Students had pillow fights occasionally. Director Weller approved as long as they did not go too far. Intra-class athletics, especially in football and basketball, provided an outlet for students. A tradition of “hazing” first-year students, known as “fuchses” or foxes, existed for many years. The “fuchses” would have to do what the upperclassmen ordered, such as shine shoes, make a bed or pump the pipe organ. The “fuchses” also had to “run the gauntlet” in the winter. Upperclassmen armed with snowballs would form a long line and pelt the “fuchses” as they ran by. Director Weller wanted “his boys” to be tough.

Enrollment grew steadily, reaching 136 students in 1916. However, World War I was costly to the “German college.” Some local “super patriots” questioned the loyalty of a few professors. The number of students dropped to 106 in 1918. As proof of the school’s loyalty to the country, the school erected what was said to be the tallest flagpole in Seward County. The new director of the school, F. W. C. Jesse, gave “four-minute” speeches in the area, a government program to support the war effort. The 1919 catalog assured its readers, “Our boys are trained for the highest type of American citizenship.” The enrollment bounced back in 1919 as the school moved forward into its second quarter century.

Dr. Jerrald Pfabe is a professor emeritus of history and serves as a Spanish professor and archivist at Concordia University, Nebraska.